Welcome to “Black Pioneers: Legacy in the American West.”

This exhibition was curated by renowned historian/author/artist Dr. Carolyn Mazloomi, one of the foremost experts on African American quilting history and traditions, in partnership with the James Museum of Western & Wildlife Art, located in St. Petersburg, Florida. It features 50 original quilts made by members of the Women of Color Quilters Network, a national organization founded by Dr. Mazloomi to foster and preserve the art of quilt making among women of color. Be sure to check out the short video in the gallery, as it gives more insight into Mazloomi’s vision for the exhibition.

Today we will take a close look at eight quilts and discuss some of the people and events instrumental in shaping the American West. Many of these stories have been omitted from our country’s historical narrative. We will touch on themes and topics such as exploration, women’s empowerment, civil rights, resilience and resistance, entrepreneurship, and community.

For those who have no experience with quilting, let’s start with the basics.

Quilts are made of three layers, like a sandwich: (1) quilt top – decorative layer, made up of fabric pieces (traditionally scraps) sewn together; (2) batting – soft, warm filler in the middle; and (3) backing – bottom layer, usually one large piece of fabric. It is the quilting, or stitching, that holds the layers together.

Quilts are often made to serve a practical purpose: to keep us warm. They can be sentimental, made with care, reflecting personal memories. The quilts in this exhibition were not made to be used as blankets. They are considered art quilts, which are meant to be displayed and appreciated as works of art.

As we move through the gallery, we will look at a variety of styles, mostly pictorial (story) quilts, but we will also see an example of an improvisational (abstract) quilt. We will talk about the artists, their unique styles, compositional choices, quilting techniques, materials – and, of course, the important and often little-known stories they depict through fabric.

This first quilt we will talk about embodies the theme of exploration. And while the exhibition focuses on the American West, this quilt has a Florida connection…

STOP 1

STOP 1

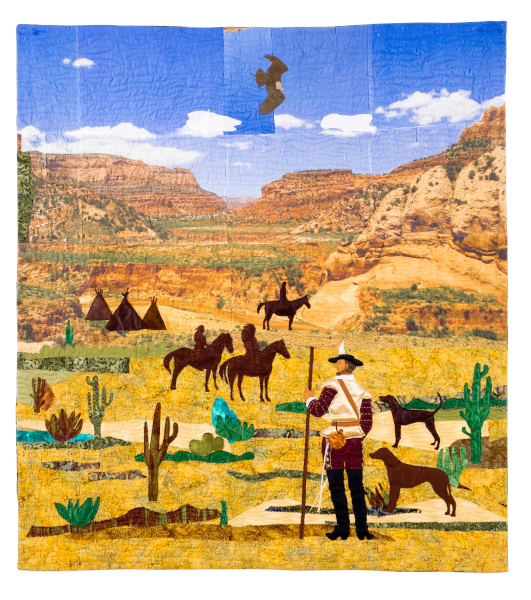

This quilt, made by Ife Felix, is titled Esteban de Dorantes: The Moor.

The artist used cotton fabric and lamé, a fabric woven or knitted with thin ribbons of metallic fiber. She included appliquéd elements (French for “to apply”), pieces of fabric cut into shapes and applied to the quilt. It is machine quilted.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 1 CONT.

The artist portrays Esteban (1500-1539), the first known African to enter what is now the U.S. Born in North Africa, Esteban was captured by Portuguese slave traders and by 1520 was enslaved by Spanish soldier Andrés Dorantes de Carranza. Dorantes brought Esteban on the ill-fated 1527 Pánfilo de Narváez expedition to Florida, which left the entrada of 300 men shipwrecked off the coast of Texas. Only Esteban and three others survived, and for the next eight years wandered the Southwest U.S. and northwest Mexico. Esteban would learn the languages and cultures of Indigenous people, skills that would serve him well as an interpreter and guide.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 1 CONT.

You may notice that the scene depicted is not completely accurate – it includes tepees, which were/are not used by indigenous people in the Southwest. Like any work of art, this is an artist’s creation and interpretation.

Regarding her creative process, Felix explains:

“… I wanted to show him (Esteban) in the foreground looking out over the vastness of this patch of earth. He had to be brave to engage with the Indigenous people and learn from them while surviving this hostile environment, not so much from natives but the colonizers. I used a variety of earth tone fabrics for the background, so the viewer feels the dryness, the still of the wind and the barrenness of the land. I appliquéd the images and added color for depth.”

Next, we’re going to jump forward about three centuries and travel to San Francisco during the Gold Rush.

STOP 2

STOP 2

Artist L’Merchie Frazier’s quilt, titled Call Me Mrs. Mary E. Pleasant: The Midas Touch, tells the story of a powerful Black woman who built a fortune for herself in 19th century San Francisco.

The artist used layer upon layer of sheer, nylon fiber to create her machine-quilted top, conveying opulence and wealth. One unique aspect is its use of digital printing, which is a more efficient alternative to appliqué. The artist uses an ink-jet or other printer to print the image onto a thin piece of paper coated with wax and pigment. A heat press is then used to transfer the image onto the fabric.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 2 CONT.

Mary Ellen Pleasant (1815-1904) was an entrepreneur, financier, real estate magnate and abolitionist. Arguably the first self-made millionaire of African American heritage, she identified herself as “a capitalist by profession.” As a young girl, she was sent to Nantucket to work as a domestic servant. After her first husband died and left her a considerable inheritance, she left New England for San Francisco at the height of the Gold Rush in 1852. Pleasant worked as a cook and shrewdly eavesdropped on the wealthy people she served, using the information to invest bits of her inheritance. Over time she established laundries, boarding houses, restaurants, and other ventures. With the help of wealthy business partner Thomas Bell, Pleasant amassed a fortune by 1875.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 2 CONT.

Well-known and controversial, the press dubbed her “Mammy Pleasant,” a nickname she hated. She’d continue fighting attacks on her character until her death. “I got a letter from a minister in Sacramento, and it was addressed to ‘Mammy Pleasant,'” she told one reporter. “I wrote him back on his own paper that ‘my name is Mrs. Mary E. Pleasant.’ I wouldn’t waste any of my paper on him.”

The West offered opportunities for African Americans that were not available in Jim Crow South. Like Mary E. Pleasant, many made the long journey Westward to seek out new beginnings…which brings us to our next quilt.

STOP 3

STOP 3

This work by artist Marjorie Diggs Freeman is machine-pieced and hand-quilted. “Piecing” refers to the process of assembling and stitching pieces of fabric together to make a quilt block. This can be done by hand or, in this case, by sewing machine. The artist then hand-quilted (stitched by hand) the three layers to make her finished product. This quilt is different from the previous ones we’ve looked at so far. It is considered an improvisational quilt, meaning it is more free form and abstract in design, with pieces usually cut by hand. Freeman leaves viewers to interpret the meaning for themselves. Although abstract, she is telling a story.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 3 CONT.

Take a minute to stop and observe as much detail as you can. What do you think the artist is conveying?

Freeman titled this quilt Migration West. Does knowing the title change your initial observations or make you reconsider the artist’s intention? How does she tell they story of migration in her design?

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 3 CONT.

With her work, Freeman is touching on a huge migration movement in the late 19th century. One of the ways African Americans responded to the rise of Jim Crow was through migration – both to the North and West. The Exodus of 1879 was the first significant movement of Black people out of the South, with ~6,000 from Louisiana, Mississippi, Texas, Tennessee, and Kentucky migrating to Kansas, Colorado, and Oklahoma. These Black settlers were known as Exodusters.

Across the Great Plains states, about 3,500 Black people became successful homesteaders and owned 650,000 acres, building their own homes, farms, and society groups. An additional 5,000 headed West to become cowboys, participating in the great cattle drives that linked Abilene, Texas, and Dodge City, Kansas.

Continuing with the theme of promise and opportunity, we move on to our next quilt.

STOP 4

STOP 4

Moving now to a quilt by Renée Fleuranges-Valdes, titled You Belong in Oklahoma!

This is a machine pieced quilt made with cotton fabric. Notice the appliqué work, and the unusual shape of the quilt, which of course tell the story of Oklahoma. Regarding her creative process, the artist explains:

When creating a piece that requires storytelling I find it a real stretch, a challenge. The first step is to get to know the subject and decide if you are going deep into their lives or if you want to focus on one aspect. I did that by using symbolism – the megaphone, the newspaper print, the covered wagons, etc.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 4 CONT.

Edward Preston McCabe (1850-1920) had big dreams. He was a land developer and speculator, a lawyer, an immigration promoter, a newspaper owner, and a politician. He also was the only African American to ever hold statewide office in Kansas. After finishing law school in Chicago, McCabe came to Kansas in 1878, settling in Nicodemus, a town in north central Kansas established by Exodusters, the freed slaves who made their way from the ravaged South after the Civil War.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 4 CONT.

He later moved to Guthrie, Oklahoma, where he worked with other Black leaders hoping to create a state populated and governed by an African American majority. He purchased 320 acres, established Langston City, named for a recently elected Black congressman, and hired agents to travel to the South to attract new settlers. McCabe promised, through these agents, that new settlers would be coming to “the… paradise of Eden and the garden of the Gods,” and capitalized on the rapidly deteriorating conditions in the South. The recruitment campaign was a success and by 1891, the town had over 200 residents. This prospect was greeted with excitement by the Black press but was condemned by white and Native Americans.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 4 CONT.

According to the artist:

“I did find it ironic that a black man whose goal was to flood Oklahoma with black settlers, would be comfortable doing so by stealing ‘Indian’ land. To tell McCabe’s story and his impact on the westward movement, I felt I had to go as deep as my research would allow. I attempted to use his lives’ details to build the larger picture. Remember the land the government made available to settlers was really owned by Native Americans. So, I choose to build a large ‘totem pole’ with a Native American male on the bottom yet another symbol of America’s repeated history of taking what isn’t theirs, be it land or people, all to further this country’s expansion.”

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 4 CONT.

When choosing her subject for this quilt the artist chose Edward McCabe because of his obscurity:

“It seemed he came, made his mark, but like so many other blacks because he didn’t fit the ‘mold’ of the men in power he was just lost in history. The other thing that stood out to me was how he used his newspaper almost as a megaphone. He played on the poor black southerners. But his goal was not altruistic. He wanted to be governor. He had lost his bid in Virginia, so the land grab era provides him another opportunity. That is, if could persuade enough blacks to move to this new territory. A territory where they would be in the majority.”

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 4 CONT.

In the long run, McCabe ended up losing his bid for governor of the territory, but he built a legacy that provided Blacks with opportunities they wouldn’t have had in the South. The creation of all-Black towns (more than 20 in Oklahoma) allowed for African Americans to thrive peacefully and make a name for themselves in the community.

Unfortunately, this joy didn’t last in the town of Tulsa, Oklahoma, about 80 miles north of Langston. Our next quilt tells that tragic story.

STOP 5

STOP 5

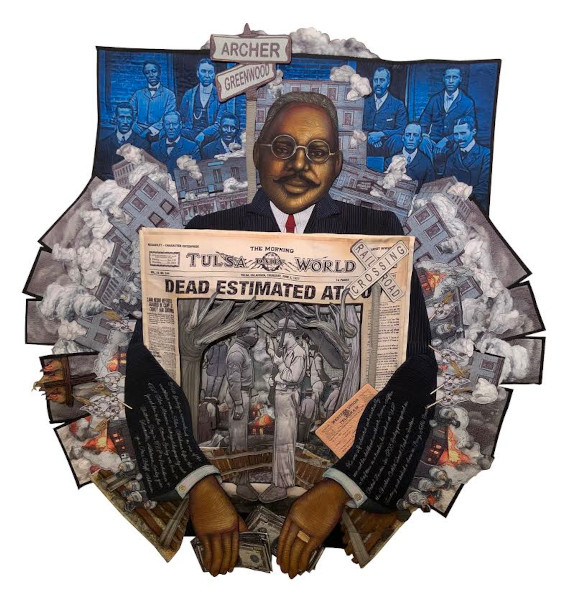

This amazingly complex work was created by artist Carolyn Crump. It is titled The Truth Hurts: Riches, Resentment, Revenge, RIOTS.

Made of cotton fabric and cotton batting, one unique aspect of this quilt is the use of acrylic paint. Crump hand-painted sections if you look closely. It is machine appliquéd and quilted, with layers of figures and imagery.

It tells the story of the Tulsa Race Massacre of 1921, which killed hundreds of residents, burned more than 1200 homes, and erased years of black success in Oklahoma.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 5 CONT.

On the morning of May 30, 1921, 19-year-old Black shoe-shiner Dick Rowland was riding in the elevator in the Drexel Building with 17-year-old white woman Sarah Page. Accounts of the events that followed circulated among the city’s white community during the day and became more exaggerated with each telling, morphing into an assault allegation. Tulsa police arrested Rowland the following day and began an investigation. An inflammatory report in the May 31 edition of the Tulsa Tribune spurred a confrontation between Black and white armed mobs around the courthouse. Shots were fired and the outnumbered African Americans began retreating to the Greenwood District. In the early morning hours of June 1, 1921, Greenwood was looted and burned by white rioters. Martial law was declared, and National Guard troops arrived in Tulsa.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 5 CONT.

Twenty-four hours after the violence erupted, it ceased. Thirty-five city blocks lay in charred ruins, more than 800 people were treated for injuries and, at the time, reports of deaths began at 36. Historians now believe as many as 300 people may have died.

Despite these devastating events, African Americans had the resilience and determination to rebuild almost immediately—in defiance of hastily-enacted racist zoning codes—giving rise to the neighborhood’s moniker of Black Wall Street after, not before, the massacre. Continuing with the theme of determination, our next quilt highlights the achievements of a trailblazing Black artist.

STOP 6

STOP 6

Many of you will recognize the figure portrayed in this next quilt. Made by Alita Aldridge, it is titled Hattie McDaniel: Oscar’s First Black Winner.

Made from 100% cotton fabrics, the quilt took the artist about six months to complete. It features raw edge machine appliqué and photo transfer.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 6 CONT.

Being a Los Angeles native, Aldridge felt it was appropriate to honor Hattie McDaniel (1893-1952), an actress, singer-songwriter, and comedian. Most significantly, she was the first Black person to win an Oscar (Best Supporting Actress in 1940) for her role as “Mammy” in the film Gone with The Wind.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 6 CONT.

Regarding her creative process, Aldridge explains:

“Blue fabric chosen for Hattie’s dress because that was the color of the dress she wore when she accepted her Oscar award. Black/white/gray scale fabrics were chosen when creating Mammy to represent the darkness in our history of enslaved servants. Mammy’s red petticoat represents a segment in the movie when she was declared a ‘Smart old soul’ and gifted the red petticoat by Rhett Butler. The Cocoanut Grove is an exact replica of the nightclub where Hattie received her award, but was not allowed to enter through the front door because of her race. The White plantation is an exact replica of the house used in the movie”

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 6 CONT.

Born in 1893 to formerly enslaved parents, McDaniel grew up in poverty. In the 1920s, she toured with vaudeville and minstrel shows, and poked fun at stereotypes by performing in whiteface. In 1931 she moved to Los Angeles, where she traded her provocative stage persona for uncredited film roles as maids and slaves. While some Black actors refused to play such characters, McDaniel pushed back in more subtle ways. Her domestics were more opinionated and defiant than most at the time. “She’s an artist who’s been resisting white domination with performance — up until she becomes involved in white show business,” says historian Jill Watts. “If you watch those performances, she’s straitjacketed [by the writing], but she’s trying to move her way out of that.”

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 6 CONT.

As for her Oscar, an appraiser at the time deemed the plaque valueless, and it was given to Howard University, where the drama department put it on display. By the early 1970s, however, the award had gone missing, and it hasn’t been seen since.

STOP 7

STOP 7

Next, we will look at Rosy Petri’s quilt, titled A Good Soldier: Thomas C. Fleming.

The piece is a combination of traditional patchwork quilting and raw edge appliqué, a technique in which motifs to be appliquéd to the background fabric are cut to the exact size needed. This quilt took Petri about a month to make. Petri’s love for journalism inspired her to depict the oldest and longest-serving Black journalist in the country.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 7 CONT.

Thomas C. Fleming was born in Jacksonville, Florida in 1907. In 1919 he moved to Chico, California. Fleming was hired as the first editor of The Reporter, a newspaper serving the San Francisco’s flourishing African American community. Fleming used his new position to campaign against racism while covering local and state politics.

In 1949 Fleming’s friend, Dr. Carlton B. Goodlett, won control of another newspaper, The Sun, and merged it with Fleming’s paper to form the Sun-Reporter. Over the next 50 years, with Goodlett as publisher and Fleming as editor and political reporter, the Sun-Reporter became the largest newspaper serving the African American community in Northern California.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 7 CONT.

As the Civil Rights Movement grew, Fleming used the pages of the Sun-Reporter to support Bay Area activism and educate African Americans about political issues. Fleming’s political reports took him to national party conventions, international conferences, and to meetings with at least two presidents, where he continued to press for the political empowerment of African Americans. He passed away in 2006, a year before his 100th birthday.

STOP 8

STOP 8

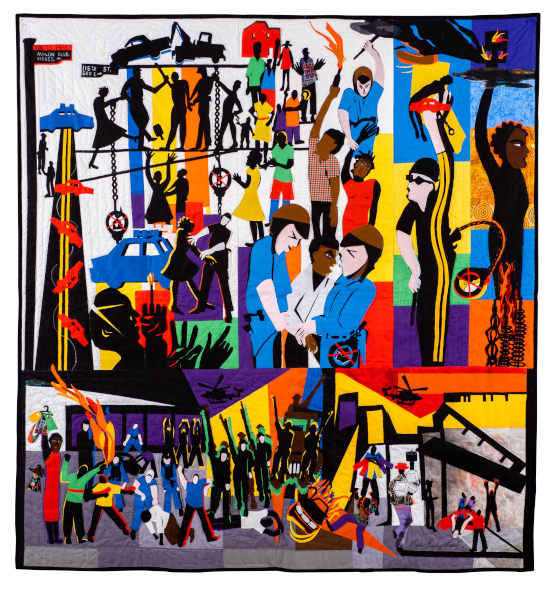

Our final stop is titled Watt’s Riot, a powerful work created by artist Viola Burley Leak that speaks to civil rights issues.

Another example of an improvisational quilt, this one is made of cotton fabric and was machine appliquéd and quilted. What strikes you most about the composition? Where does your eye land first? Notice the strong vertical lines and bold colors. Notice the diagonal lines, which artists use to create a sense of energy and action.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 8 CONT.

The Watts Rebellion, also known as the Watts Riots, were a series of riots that broke out August of 1965 in the deeply impoverished and predominantly Black neighborhood of Watts, in South Central Los Angeles.

On August 11, Marquette Frye, a young Black motorist, was pulled over and arrested by Lee W. Minikus, a white California Highway Patrolman, for suspicion of driving while intoxicated. As a crowd of onlookers gathered at the scene of Frye’s arrest, tensions between police officers and the crowd erupted into a violent exchange. This outbreak of violence immediately touched off a large-scale riot over six days, during which rioters overturned and burned automobiles, and looted and damaged grocery stores, liquor stores, department stores, and pawnshops.

(Continued on the next slide)

STOP 8 CONT.

Over the course of the six-day riot, more than 14,000 California National Guard troops were mobilized in South Los Angeles and a curfew zone encompassing over 45 miles was established to restore public order. In all, 34 people were killed, more than 1,000 injured, and almost 4,000 were arrested before order was restored on August 17.

The riot was a result of the Watts community’s longstanding and growing discontentment with high unemployment rates, substandard housing, and inadequate schools. Despite these findings after the riots, city and state officials failed to implement measures to improve social and economic conditions in the neighborhood.

Thank you for visiting Black Pioneers: Legacy in the American West.

To learn more about Black history at the California Museum, check out our Black History Self-Guided Tour.